James: “We will leave the studio go into the apartment get an acoustic guitar and play the song from beginning to end, like you would at a campfire. And if the song doesn’t work that way, then there is something wrong with the song itself you know? You should never have to hear a 4 bar filter sweep for the song to work.”

Composition-wise, where do metric songs typically come from? Do things usually get started by writing songs on a piano or a guitar? Or do songs develop out of finding the right synth tone or rhythm track?

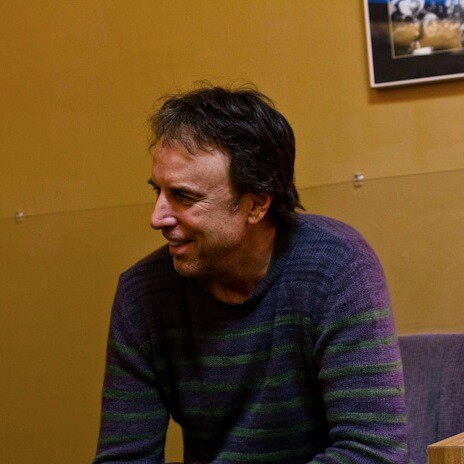

You know its weird it happens in a lot of different ways. Both of those things definitely happen. We played a show in Toronto a couple nights ago, like a big, free show. We flew into Toronto that day, played the concert, stayed out late, woke up — and I kind of did that thing where you wake up way too early in the morning. And I walked back to Metric studio, which is behind my house, because I hadn’t been in there in a couple of weeks. I turned everything on and the next thing I knew I was playing four synths at one time. And the moog was going, giving like a pulse-y kind of bass line. And I was like ‘the car is going to show up in 5 minutes to go to the airport, I’ve got to boot up pro tools so I can record this. And every once in a while that happens. Every once in a while you are playing chords on a acoustic guitar and that happens. For me probably the most common thing is I’ll actually be walking down the street somewhere on my own, and hear something, and kind of dream up the whole thing and keep it going in my head, just kind of write the whole thing in my head. Then I will go into the studio and pick up any instrument and kind of jot it all down. And then try and make it sound half decent, and send it to Emily somewhere, and she’ll write some lyrics and words. I’m not really a lyrics guy. I write melodies but not really that many words.

The production on this Fantasies record, seems to balance an interesting tension between the songs, which sound like the might be able to be played solo on a guitar or piano, and the arrangements, which carry all of these big sweeping dance elements, and dynamic shifts. When you all approached producing or recording these songs, were you conscious of this interplay between the song and the arrangements? Or were you just doing what sounded right at the time?

It was really something we focused on. I mean in terms of like, a color palette, we really listened to like a lot of David Bowie records. He has this incredible ability to almost go into a whisper where like he’s telling you something really important, and then the next word he steps back 10 feet and just belts out. The dynamic range is unbelievable and we were really inspired by that and wanted to get same of that same range happening. And in terms of the songwriting, we had this sort of litmus test we used called the campfire test. We are a rock band, we do a lot of production, there’s a lot of sounds and different things happening. But we wanted to make sure that those things weren’t compensating for mis-used songwriting. So when we would get halfway down the line with a song, if there was anything that was not really working, and you’d have to resort to some piece of outboard gear to make a section of a song start working – [We would] leave the studio go into the apartment get an acoustic guitar and play the song from beginning to end, like you would at a campfire. And if the song doesn’t work that way, then there is something wrong with the song itself you know? You should never have to hear a 4 bar filter sweep for the song to work. It should never have to be that way, Unless your Daft Punk (laughs). In which case that is cool too. But we were going for a level of songwriting we hadn’t done before.

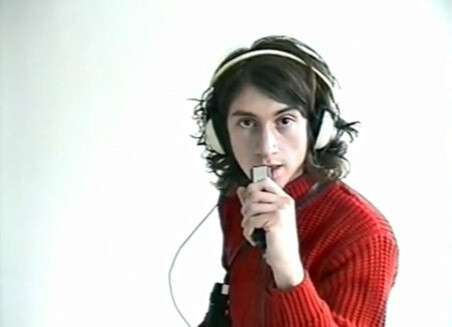

Did you have time in your life when you younger, maybe it was a few years of your life, or 5 minutes on some odd Monday afternoon, when you heard a bit of music and thought, “I’d like to try and make something like that?”

Well for me I was raised as a classical trumpet player. I got into this music school in Philadelphia when I was 16, halfway through high school. So I split town and ended up going to Juliard and playing with the New York Philharmonic, by the time I was 18. So as a kid, all I heard was classical music. And that was where I was going. Then by the time I was at Juliard, and I was 19 or 20, and I was living with the singer from Stars, Torquil Campbell. I’ve know him since I was a kid. He had this intense record collection. These two things happened at the same time: I got really disillusioned with the world that classical music lives in, because they don’t allow anything new to happen. They don’t allow you to express yourself differently musically today than you have to tomorrow. You are not allowed to express your emotions. You have to express the emotions of the conductor and what he has predetermined that the composer was feeling 285 years ago. Which to me felt very very stifling. It wasn’t something I wanted to dedicate my life to at that point. And at the same time I was hanging out with this guy Torquil who had this insane record collection. And he started playing me Primal Scream Screamadelica, and all the Smiths records, and New Order records and Nirvana records, and stuff I didn’t really know. Like I knew they were around but I didn’t know them well. It was really when I started listening to that stuff that I thought “I want to make that. I want to make that.” I sold a bunch of my trumpets, freaked all of my teachers at school, got an 8 track reel to reel, a guitar a synthesizer, a drum kit, and just set it all up in my little apartment on 58th street in New York and just learned how to try and write songs.

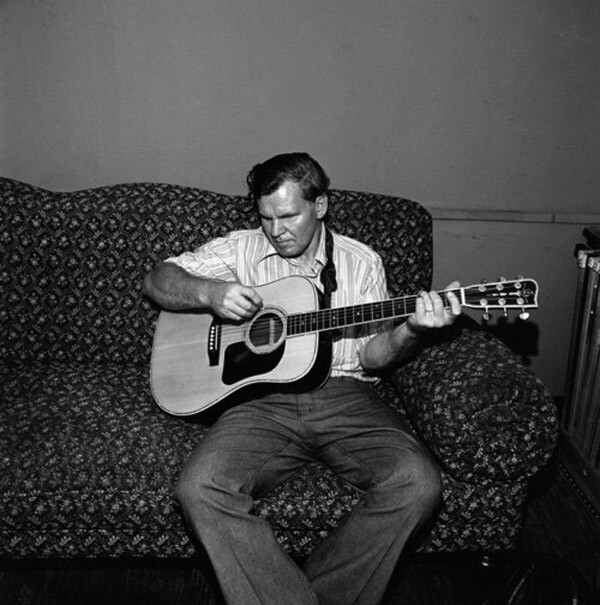

Who were some of the songwriters or bands during that time you were listening to and thinking, “These people know exactly what they are doing?â€

Honestly for me, without any level of embarrassment, it was Steely Dan. Because those guys, and the level of songwriting — coming from classical music, where simplicity was sort of shunned, there was an element of Steely Dan that I was truly enamored by. There must be 200 changes in every single Steely Dan song and yet the melody and the lyric are so visual and memorable and effective, in terms of a pop song. I’ve never really listened to Steely Dan and said “I want to make that sound” But there was something in there that made me want to find my own.