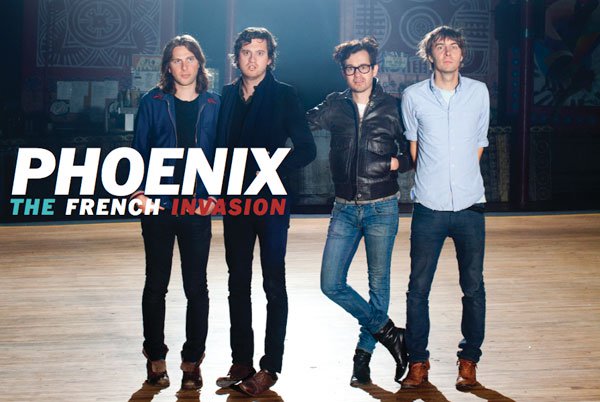

Skip Matheny— currently a songwriter in the band Roman Candle and former bartender in a retirement community — caught up with the 4 members of band Phoenix before their show at the Tabernacle in Atlanta this past April.

Online Exclusive: This is a full transcript of this text of the Cover Story: Phoenix: The French Invasion, which includes several questions, answers, and photos not available in the print edition of this interview.

During the past 12 months, the band Phoenix has made one of the more proper, and satisfying, foreign invasions on American music in recent memory. With their fourth studio album, Wolfgang Amadeus Phoenix, these four childhood friends from Versailles, France, provide a near perfect example of a group getting exponentially better at what they do with every record. The were the most-blogged-about-band of 2009, and captured the Grammy for best alternative album. Their particular brand of indie pop/rock has given discerning hipsters, soccer moms, frat guys, and kindergarteners the opportunity to dance to the same record. Sitting down with Phoenix in Atlanta to talk about their writing process, I was surprised to see just how much of a band they are. I’ve listened to them for years, but never once thought of them as four individuals who seem to make almost every musical decision as a unified group.

photos by Julia Davis & Timshel Matheny

Band Members

TM: Thomas Mars [vocals]

CM: Christian Mazzalai [guitar]

DD: Deck D’Arcy [bass]

LB: Laurent Brancowitz (Branco) Â [guitar]

What’s your favorite drink?

TM: Oh we have many. I love Mint Julep. We were in Kansas City and had Mint Juleps. That was nice.

That’s a great drink. There is a great recipe in an essay by (American author) Walker Percy that was printed in Esquire magazine years ago.  The essay was called “Bourbon.â€

TM: Now it makes me want to go to the Kentucky Derby. Â We had it in a silver cup. Very chic.

CM: Sake.

LB: Sake – My brother (Chris) and I are really into that. (laughs) My theory is it’s the only alcohol that has a poetic quality to it. But one time I drank too much and I played really bad.

DD: That’s true, but you were very funny.

LB: It was a good show (laughs).

Deck: I like water. I drink wine but I don’t drink it too much because it makes me tired. I love beer I have to say. Yesterday we had something very good with strawberry and bourbon.

You all were in Nashville yesterday right? Did you go to the Patterson House?

DD: Yes that was it. (pauses) Actually cocktails are very good. (laughs)

I saw an acoustic performance that you all did recently where you played with two acoustic guitars and a keyboard. I believe that you mentioned that particular setup being the way you all write songs, properly as a band. Is that true for the most part? Do you typically write songs with a more stripped down instrumentation and then take it into a studio, to fill out the rest?

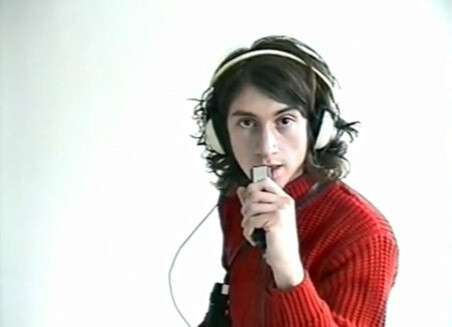

CM: Yeah. We use very cheap keyboards and acoustic guitars and tape recorders—a Dictaphone. We record for hours and hours.

TM: It is always with cheap instruments—very, very cheap, like 20 dollars—or something rare and expensive. No in-between (smiles). I guess it helps us, you know, with the keyboards. If you try something different and it breaks—it doesn’t matter because it’s not valuable. So you have this freedom to use them the wrong way.

LB: When they are really cheap, they breathe, you know? They have this hum. You know the children’s samplers? We use them a lot. They almost sound like a very expensive Mellotron. We also have very good synthesizers, and they breathe too.

DD: We like everything that alters or filters your original idea. That’s why we work with very cheap equipment. We also work with cheap recorders when we compose. [Even though] it’s not supposed to sound like this on the record, it kind of fantasizes everything. So when you listen back to it, it gives you a very new vision of what you did.

Yeah – I love how digital recorders influence the sound of the thing they are supposed to be documenting – it adds a lot – even in the way it collects the sound of the air in the room.

DD: Yeah exactly. This is what we like – It’s very compressed and everything sounds…

LB: …less precise, you know?. You can project –- when you listen back — you can imagine things that aren’t there.

Are there any particular songs from when you were younger — or from last week maybe — that have inspired you to create music?

TM: There are so many songs. Maybe The Ronettes’ “Be My Baby†in a way is the ultimate. I listened to it again yesterday. I’m always asked, “What’s your number one?†If there was a number one, that would be it. Because of the second verse. When you hear the beginning of the second verse — the confidence and the smile — and they are backed up with this incredibly nostalgic atmosphere — I mean it’s — yeah, “Be My Baby”.

LB: I always wanted to create things. I remember jokes in kindergarten—I realized that someone created that. I loved this idea. So songs — we love music because it is the most powerful (pauses) black magic. It is really mysterious yet it works on almost everyone, you know? It just reaches people somewhere and nobody really knows how it works. So the reason [we make music is] is –- lust for power? (laughs) Because it’s so powerful. I think that every form of creation is equal – if it’s building a chair – it’s just that some forms of art are more powerful, or have more direct power. But the act of creation is the same.

As for songs, we were ten years old when Thriller was released. And Thriller was a shock for the world, for everybody –even now I don’t really understand how it works. It’s like all the seams have been removed, and it’s this mysterious sphere or monolith. You can also feel that it’s the result of a tradition. A tradition of secrets and a tradition of expertise. And this is very important to it, to every form of art in the fact that you have this heritage. When you have that, of course there is this desire to create something new, but there is a tension between creating something new and this form [that is passed down].

Who are some other artists you listen to that you think are aware of this type of tradition?

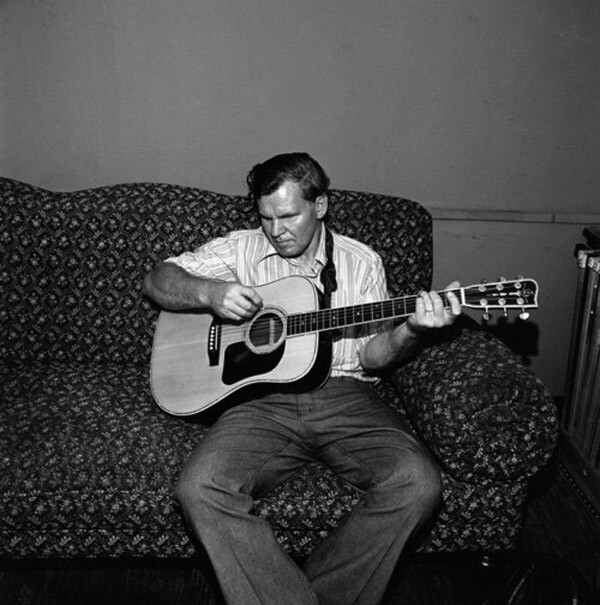

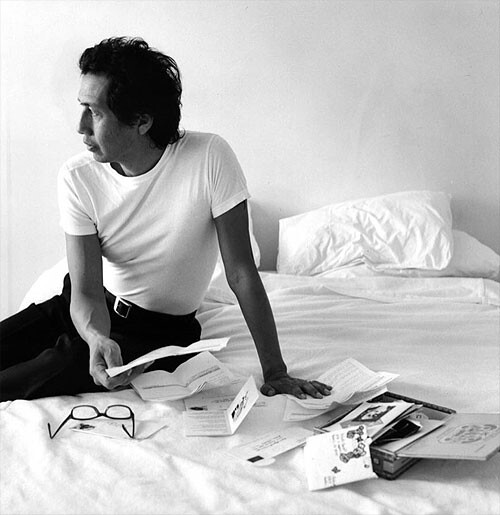

LB: Bob Dylan is a good example, because he knows the rules. You can feel that he worked. But then he knows how to bypass, to destroy the rules. And he kind of knows how to talk to people’s subconscious, you know? Kind of knows the secret language of the subsconscious I think. And he knows the traditions – and then he tries to hide the fact that he knows. (laughs)  He is a very good guitar player. But he plays it as if he was bad. (smiles) Which is cool.

LB: When you listen to his early recordings, he is really, really good. He knows what he is doing and he is 18 or something. Which is really weird—because he knows the secrets of the old people. The Velvet Underground is a good example. When you listen carefully it’s just country and western licks, but it doesn’t sound like country and western. [Laughs]

Often, bands have primary songwriters and they bring songs for the group to translate. Listening to your demo collections The Wolfgang Diaries, I didn’t get the sense that these sketches were coming from one person’s brain.

TM: I think that is what’s different about us; it’s really the four of us. It’s a mystery to us because it’s all about this chemistry, so it’s really hard to point out when a song comes out, or when the inspiration is there or…

CM: …Or who begins a song. We have forgotten everything—I don’t remember who wrote the verse of it or thought up the beginning of the song. It’s sort of blurry. We are all together and then [snaps his fingers], there is a moment. And I think that’s how we write, really. The recipe is blurry, and when we don’t understand things, that’s when the creation begins.